Natalie Gubbay is a rising senior from Wellesley, Massachusetts. She is a Mathematical Economics major, avid gardener, and works at Colorado College’s Quantitative Reasoning Center. She loves hiking, cooking, and, depending on the day, math problems. Natalie is looking forward to exploring questions of environmental justice while spending the summer in beautiful Colorado!

Meet the Fellows: Britta Lam

Britta Lam is a rising senior from Hong Kong who is double majoring in Environmental Policy and German Studies. She is currently working as one of the Events Interns under the Office of Advancement and is also the president of the Consulting Club on campus. She is interested in environmental consulting, environmental law, electric vehicles, and energy markets. In her free time, she plays pickup basketball with friends.

Meet the Fellows: Luci Kelemen

Luci Kelemen is a rising senior studying integrated environmental science. She is from a small town just north of New York City, but is an avid Red Sox fan. In her free time, she likes cooking with friends and hanging out with her dog. Luci is very excited to be working with State of the Rockies this summer as the project represents an incredible opportunity to dive into her passions. She hopes to have some nice barbecues with the Rockies cohort in the coming months!

Meet the Fellows: Lily Weissgold

Lily Weissgold is a rising senior from Burlington, Vermont. She is double majoring in Microeconomics and Environmental Policy. She currently serves on the Trails Parks and Open Space committee for the city of Colorado Springs. In her spare time, Lily enjoys reading the New Yorker, baking bread, and enjoying the Colorado sunshine. She is very excited for her Fellowship and to conduct academic research on a community about which she cares so much!

Climate change, public lands take center stage at Denver’s Outdoor Retailer trade show

DENVER • Outdoor Retailer’s winter extravaganza returned to the Mile High City for a second January since the move from Utah, where tradespeople felt betrayed by the state government’s support of shrinking national monuments.

Once again almost 900 exhibitors filled halls and ballrooms this week, and once again industry representatives used offshoot meeting spaces at the recreation industry’s premier trade show to rally for the protection of public lands.

Editor’s Note: Over the next year, The Colorado Independent will examine, season by season, the effects climate change is having on the state’s water supply and the many forms of life it sustains.

Every time Stella Molotch finishes a run down the ski slope at Steamboat, her dad Noah slips two Skittles into her tiny hands. It’s a reward – yet another step forward as the six year old is learning to ski.

People across the Rocky Mountain ranges long have quipped that kids here often learn to ski before they know how to walk. But these days, this powder-based parenting style is increasingly born out of necessity rather than impatience.

CC Students Deploy Journalistic Method, Attempt to Uncoil Complex Environmental “Rattlesnakes” of the West

CC students investigate air, land, and water issues with visiting reporter

As a reporter for the Denver Post, Mr. Finley covers environmental struggles that shape our lives in the West. Just like real reporters, students follow Finley into the field to learn how to find a story. They learn how to gather information through an objective process of verifying, analyzing, and assimilating the facts. During this block 3 GS 233 course students will sharpen critical thinking and writing skills while grappling with complex environmental challenges of living in the western United States.

CC State of the Rockies fellow Dave Sachs ’18 chats briefly with visiting professor Bruce Finley. Watch the video to hear their conversation.

CC Group Traces H2O Flow from High to Low

Field Studies, Sustainability, State of the Rockies Project look at how siphoning water from mountain headwaters enables Front Range urban growth

Colorado College students, staff, and faculty devoted this year’s first block break to exploring gold-dotted Continental Divide mountainsides where Colorado Springs Utilities’ moves water through an intricate re-engineering of natural flows. A complex system of reservoirs, pipelines, and pump stations delivers water sourced from the Continental Divide to people 100 miles away .

The State of the Rockies project collaborated with the Field Studies and Sustainability departments to run this fourth annual Sense of Place water tour.

“It’s important for students to have an opportunity to learn about one of the most pressing socio-environmental issues facing the Rocky Mountain West,” State of the Rockies director Corina McKendry said.

Why learn about water issues in the West? “I think it’s important particularly in Colorado because water in the western United States is such a permeating issue. So much of our lives hinge around this important and scarce resource and the way we move it from one side of the continent to the other has far-reaching impacts,” said Sustainability director Ian Johnson.

This CC group explored Colorado Springs Utilities sites by day, and by night soaked in the Mount Princeton Hot Springs pools under starry skies. The group also investigated how water plays a central role in Colorado’s outdoor recreation industry, inspecting the Salida river walk where tourism, fishing, and rafting sputter without sufficient streamflow. At the Larga Vista Ranch in Pueblo, the group explored the use of water in agriculture. Finally, the group toured a Colorado Springs water treatment plant where officials discussed the operation of reusing water and the process to ensure water quality.

As in many western cities, water is a social, political, and environmental challenge. In as early as the 1870s, the city began storing runoff from nearby watersheds and transporting it by pipeline to meet customer demand. Over the last 150 years, Colorado Springs Utilities has expanded the water collection system to include transmountain sources from 100 miles away delivered through an efficient network of 4 major pipelines, 7 collections systems, and 6 water treatment plants.

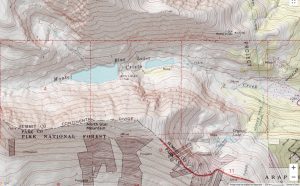

At 9,230 feet, Crystal Creek Reservoir is one of three Pikes Peak north slope reservoirs. Built in the 1930s during the Great Depression, these reservoir projects were part of the government’s effort to create jobs in the region.

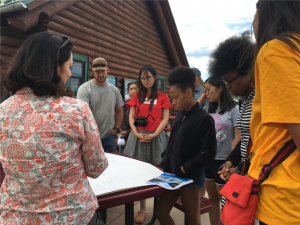

From the Crystal Creek Reservoir visitors’ parking lot, Kalsoum Abbasi, water conveyor engineer for Colorado Springs Utilities and 1997 Colorado College alumna, pointed to the plan view of reservoirs and pipelines of the local water supply system while students, Mowei Jiang ’21, Zaria Taylor ’22, Daya Stanley ‘22, Kelly Yue ’21, and Tia Vierling ’22 looked on with curiosity. She explained how water is transported from Crystal Creek, North Catamount, and South Catamount reservoirs via gravity to water treatment plants further down the mountain. Ms. Abbasi’s job is to make sur e that every time a customer turns on the tap, clean water comes out. She analyzes mountain snowpack levels and weather forecasts each spring to anticipate how much water Colorado Springs Utilities can divert safely so that downriver farmers’ and other users’ legal rights to withdraw water are also satisfied.

e that every time a customer turns on the tap, clean water comes out. She analyzes mountain snowpack levels and weather forecasts each spring to anticipate how much water Colorado Springs Utilities can divert safely so that downriver farmers’ and other users’ legal rights to withdraw water are also satisfied.

The Fountain Creek Watershed is the city’s natural watershed. It has the capacity to support a population of only about 50,000 people, but with the development of the 1870-1960s local water supply system, which includes diverted water from the north and south slopes of Pikes Peak, the Northfield and South Suburban systems, and the Monument Creek diversion, about 20% of the city’s water needs supplies are met annually.

High on the western slope of the Continental Divide, completed in the 1950s at 11,000 feet, the Blue River project was Colorado Springs Utilities’ first transbasin water diversion venture.

When the call comes to move water, Blue River watershed operator Kurt Fishinger responds with a turn of one of these iron wheels at the Monte de Cristo diversion. A turn of the wheel on the right side of the platform diverts water from the Blue River watershed through Hoosier Tunnel, a 12-foot 1.5 mile-long tunnel, to the eastern slope of the divide for use by the US Air Force Academy.

When the call comes to move water, Blue River watershed operator Kurt Fishinger responds with a turn of one of these iron wheels at the Monte de Cristo diversion. A turn of the wheel on the right side of the platform diverts water from the Blue River watershed through Hoosier Tunnel, a 12-foot 1.5 mile-long tunnel, to the eastern slope of the divide for use by the US Air Force Academy.

With a turn of the wheel on the left side of the platform, the water is returned to its native watershed and ultimately on into the Pacific Ocean.

The Montgomery Reservoir, elevation 10,873 feet, was constructed as a storage terminal for the headwaters of the South Platte River. Water diverted from the Blue River system through the Hoosier Tunnel is also stored in Montgomery Reservoir and is an important contributing source of water for The Homestake system.

At the Montgomery Reservoir valve house, water not in immediate demand is returned to its native course. Water is manually diverted by opening pipeline valves and spillways. Gravity pulls water through the 78 mile-long network of steel pipes of the Blue River water transport system. While constructing the Blue River water supply system, Colorado Springs Utilities worked to acquire rights and to design a joint venture construction project, the Homestake Project, which would serve both Colorado Springs and the city of Aurora, Colorado. The two cities share equally the costs and production of water supply.

Colorado College staffers Inger Bull and Mae Rohrbach, faculty Anthony Bull, and watershed operator, Kurt Fishinger peer deep into the darkness of Hoosier Pass Tunnel.

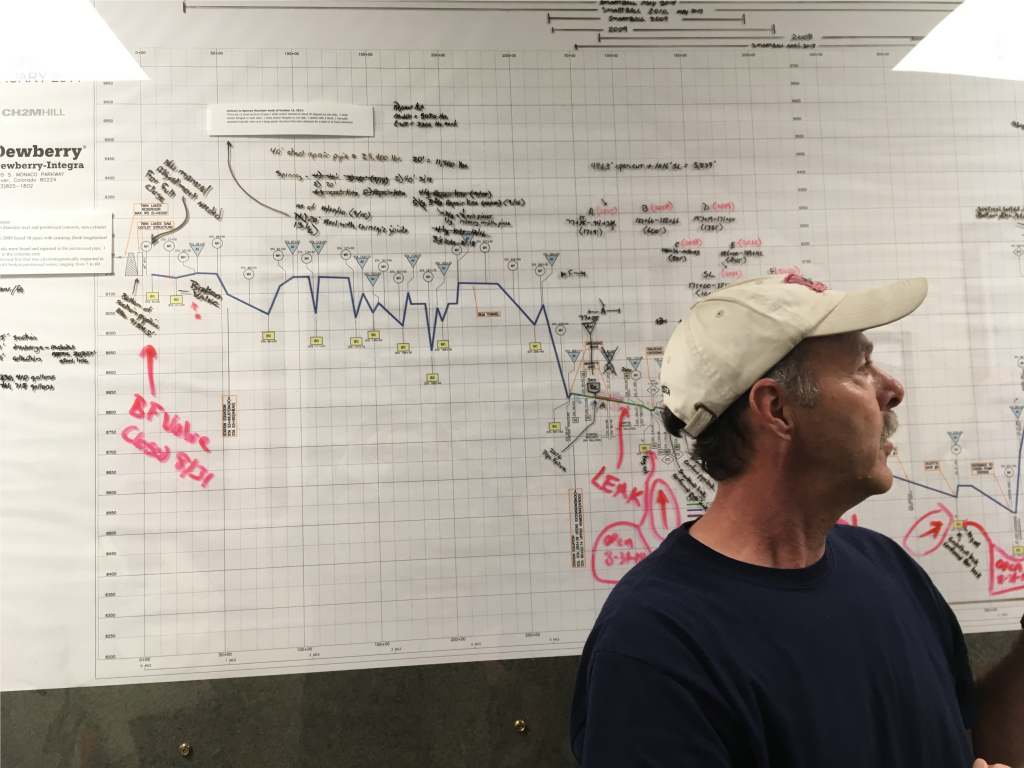

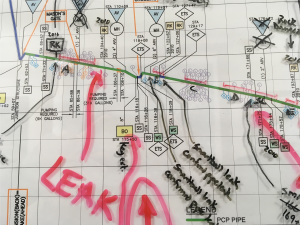

Superintendent Tom Hankins of the Homestake Otero pump station lives on-site approximately 100 feet away from the facility. He and eight station employees use state of the art smart balls, computer technology, and machinery to locate and monitor leaks in the pipelines and repair breaks caused by extreme cold mountain temperatures and pressure needed to pump the water over the mountains to Colorado Springs and Aurora customers. Tia Vierling ’22, asked Mr. Hankins how many of the employees were women. None.

At the Otero pump station, Kelly Yue “planks” in one of the 66-inch diameter concrete pipes that comprise the Homestake system. In 1962, the cost to build the Homestake system pipeline was $300,000 per mile. Today, construction would cost 10 times more. “To permit this at this day and age would be really difficult,” Tom Hankins said. The politics would be brutal not to mention nearly impossible to acquire the water rights. “Water rights are so American,” said Kelly, a second-year student at Colorado College. “In China, water is shared and not considered a commodity.”

“Most of our students aren’t from Colorado and probably don’t know much about water law or trans-mountain diversions, so I think it’s an important thing to see and come to terms with. If we’re going to care about a place and work to make it sustainable, that starts with asking questions and seeking to understand. ‘Where does our water come from?’ is an easy place to start that process with anyone who is new to this area, or anyone who has never thought about these sorts of issues before,” Ian Johnson said.

“Most of our students aren’t from Colorado and probably don’t know much about water law or trans-mountain diversions, so I think it’s an important thing to see and come to terms with. If we’re going to care about a place and work to make it sustainable, that starts with asking questions and seeking to understand. ‘Where does our water come from?’ is an easy place to start that process with anyone who is new to this area, or anyone who has never thought about these sorts of issues before,” Ian Johnson said.

State of the Rockies Conference 2012: Final Session of Conference on 4/10 highlighted Colorado’s Stake in the Colorado River Basin

Government agencies are aware of the concerns that the Colorado River won’t have enough water to meet legal obligations in coming years and are working to avoid that scenario, three industry experts said during the final presentation of the 2012 Colorado College State of the Rockies Project Conference.

Held April 9-10 on the campus, the concluding event Tuesday night featured a lineup of:

- Water Attorney Jennifer Gimbel, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board

- Colorado College alumnus Chris Treese, external affairs manager for the Colorado River District

- Eric Hecox, section chief for Colorado Water Conservation Board’s Water Supply Planning section

All spoke on the topic: “Colorado’s Stake in the Colorado River Basin: Managing Colorado’s Water for the Next Generation.”

Water: Front and Center

This is the year to focus on water, Gimbel said. Not only has Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper proclaimed 2012 as “The Year of Water,” several important anniversaries are being observed to commemorate long-standing commitments to ensuring sufficient water supply and acceptable quality. Her organization turns 75. The agency Treese works for will be 25.

And this marks the 90th year since the Colorado River Compact was signed. The agreement between the seven states of the river basin is a compromise of how the water should be allocated and includes depletion requirements. A treaty with Mexico was added in 1944.

New guidelines established in 2007 allow more flexibility within the existing framework of the Law of the River — the various legal mandates, decrees and court decisions governing the Colorado River Basin.

Shortages, meaning less water in the Lower Basin than the Compact allows, won’t happen until at least 2026, according to Gimbel. But some expert studies predict that by 2050, climate change and burgeoning uses of the river system will result in inadequate water to meet all of its allocated shares two-thirds to nine-tenths of the time.

Gimbel used this analogy: “It’s like a train coming at you at 3 mph. If you can’t get out of the way, it’s your own fault. We can see it coming, and it doesn’t mean we aren’t trying to do anything,” she said.

Already there are supply and demand imbalances, she said, “So we have to be paying attention.”

Drought conditions, rising temperatures and other factors have decreased the river’s water supply but reservoirs, such as Lake Powell and Flaming Gorge have helped in dry times, the speakers said.

Colorado River water extends far and wide, from faucets in Los Angeles to Phoenix. While there are competing interests for drinking, irrigating crops, energy development and other industrial uses, recreational activities and protecting the environment, the speakers believe solutions are at hand.

“It’s all about putting the water to beneficial use and sharing it,” Treese said. “Compromise, consensus and collaboration are very messy and time consuming, but they beat litigation.”

Decades of lawsuits involving Denver Water’s quest for additional supply, which serves about 1.5 million customers, have given way to new approaches, such as a water bank to ensure that human health and safety needs are met, and viewing the river as a whole system, including the riparian areas and native habitats.

Efforts are underway to protect supplies, including a salinity control program, which Treese said costs up to $50 million annually but yields $376 million annually in benefits.

“The program is working,” he said. “It means we have lettuce on our table in January.”

The Time Is Now

As the last speaker at this year’s conference, Hecox issued this warning: “Colorado faces significant and immediate water supply challenges.”

And if nothing changes, agricultural water allotments would be at risk of being sacrificed for municipal and industrial needs, he said.

“If we want to avoid that we’ll have to implement a mix of strategies,” Hecox said. “We’re not going to be able to conserve our way out of it.”

Losing agricultural irrigation, however, is generally considered unacceptable, he said, for economic and food security reasons. So preparing for climate change and population growth (Colorado is expected to have 10 million residents by 2050, twice as many as today) with innovative planning and water management is underway, he said, adding that, contrary to popular belief, water does not create or stop growth. Jobs do.

2012 State of the Rockies Conference: On 4/10 Governor Hickenlooper addressed youth and the future of Colorado’s water

While there’s no “single silver bullet” to solving the challenges facing the Colorado River Basin, Gov. John Hickenlooper said Tuesday that conservation will help ensure adequate water supply in the future.

“Our discipline around how much water we use is going to be the foundation of everything we do,” he said April 10, as a guest speaker at Colorado College’s annual State of the Rockies Project Conference.

For the past year, a team of Colorado College faculty and students have been examining issues pertaining to the Colorado River Basin, which starts in Wyoming and flows across seven southwestern states into Mexico, where the delta is now imperiled from numerous dams and diversions. Persistent drought, higher temperatures and other factors also have contributed to a decreasing water supply, at a time when demand is increasing from multiple interests.

Hickenlooper congratulated the students on the project and its findings, which five students outlined before the governor took the podium.

“You should be proud of the work those students have done – it’s very impressive,” he told Professor Walt Hecox, faculty director for the State of the Rockies Project, now in its ninth year.

The action steps students recommend in the 2012 State of the Rockies Report Card, which was released at the April 9-10 conference:

- Modify and amend the “Law of the River” to build in cooperation and flexibility, to remove the competition among users.

- Recognize the finite limits of the river’s supplies and pursue a “crash course” in conservation and water distribution.

- Embrace and enshrine basin-wide “systems thinking” in the region’s management of water, land, flora, fauna, agriculture and human settlements.

- Give “nature” a firm standing in law, administration and use of water in the basin.

- Adopt a flexible and adaptive management approach on a decades-long basis to deal with past, present and projected future variability of climate and hydrology.

Hickenlooper said he’s been a conservation advocate since he first took public office as Mayor of Denver in 2003.

“I tried to convince people by them using less water and keeping more water on the West Slope that they had a direct benefit — the better it is for people living in Denver and Colorado Springs and Fort Collins and Pueblo,” he said. “It’s not just skiing and white-water rafting. It’s farming and ranching and home values. A home on the Front Range (of Colorado) is worth more than Kansas City or Indianapolis.

He challenged students to bring “youthful exuberance, creativity, optimism and technology” into the picture to help address water supply and competing water rights interests for agriculture, drinking water, the environment and recreational activities.

“A lot of it is our own self-motivation or discipline (to conserve water). How do we make it joyful and give people a kick out of it? I think that’s where youth come in — young people always have a fresher way, a funnier way, a more interesting way of looking at almost everything,” he said.

Hickenlooper favors taking a cue from how other countries are testing new innovations to save water. Israel, for instance, he said, is using drip irrigation for almost all of its crops and is toying with using brackish water on certain crops.

“Conservation is the core of what we’re talking about. We need to make sure we don’t take any more water than is necessary from the West Slope,” he said.

In response to a student asking about preserving and replenishing underground water reserves, Hickenlooper said some cities, including Denver, are doing that.

“In Colorado, there’s great recognition that groundwater is precious. The key is to integrate the different water systems, with water providers talking to each other to do that,” he said.

Molly Mugglestone, project coordinator for Protect the Flows, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting the Colorado River, followed the Governor’s address. Her advocacy group already is working on most of the CC students’ recommendations for preserving the Colorado River, she said.

The organization represents a coalition of nearly 400 businesses that depend on the river for their livelihood, from rafting companies to ski areas to fly fishing shops to outdoor retailers. About 800,000 jobs rely on the river, Mugglestone said, representing a multi-billion dollar recreation industry.

The group will release an economic impact study in May, which will demonstrate the economic value of recreational activity supported by a healthy Colorado River, she said, and is advocating on federal and local levels for recreational needs to be considered in water management decisions.

The organization’s website is www.protectflows.com.

The entire Colorado College 2012 State of the Rockies Report Card on “The Colorado River Basin: Agenda for Use, Restoration and Sustainability for the Next Generation” can be viewed at http://www2.coloradocollege.edu/stateoftherockies.

Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar, Director of U.S. Geological Survey Marcia McNutt speak at Rockies Conference on 4/9/2012

Protecting the environment and developing the economy can go hand-in-hand, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar told this year’s State of the Rockies Project Conference attendees in his keynote address April 9.

“When people say we have to choose, it’s a false choice. We can do both — we’re doing it here in Colorado,” he said. For example, “We know Colorado Springs and Denver will never grow together because hundreds of thousands of acres in Douglas County have been protected, and ranching life will be sustained,” Salazar said.

The annual conference is the culmination of the Colorado College State of the Rockies Project, a collaborative effort by faculty and students to examine issues affecting the environmental, social and economic health of the Rocky Mountain region. This year’s focus: “The Colorado River Basin – Agenda for Use, Restoration and Sustainability for the Next Generation.”

Students spent nine months studying the 1,400-mile river that extends across seven southwestern states, from Wyoming into Mexico. Their findings – that increasing demand and decreasing supply – will lead to severe water shortages in the future, and five action steps to take to prevent that from happening, were released at the conference’s opening day as well.

Salazar, who earned his undergraduate degree in political science from CC in 1977 before moving on to become a water and environmental law attorney, Colorado’s Attorney General and a U.S. Senator for Colorado, said he’s long touted a conservation agenda in conjunction with achieving economic goals.

“People would say, ‘Why are you concerned about conservation?’ I’d say, ‘It’s about the quality of life.’ And the conservation ethic we’ve been able to develop has given us great promise for economics in the future. It’s the same argument I’ve used in Washington, D.C.”

At the request of President Obama, Salazar is leading a “21st century conservation agenda” for the nation, known as America’s Great Outdoors initiative. It has three focuses. The first involves major restoration projects on 200 rivers, including the Colorado River. The creation of a National Water Trails System, which Salazar announced in February, is part of the improvements. The new network will increase access to water-based outdoor recreation, encourage community stewardship of local waterways and promote tourism.

Expanding urban parks and improving national landscapes through grassroots conservation are the other areas of concentration.

“When talking to the President, I describe it (the initiative) in ways I think accomplish both economic goals and a conservation agenda at the same time,” Salazar said, citing as an example preserving 1.1 million acres of tall grass prairies in Kansas to safeguard ranching as a livelihood, along with the native plants.

“It’s important that we protect our planet,” he said.

As a fifth generation Coloradan, Salazar said he’s familiar with the problems associated with the Colorado River.

“The Colorado River is already a water-short river — more water has been allocated than what that river has today, not only along southern states but with the treaty with Mexico,” he said, adding that a new allocation agreement with Mexico could be announced soon.

The river supplies about 25 million users with drinking water and irrigates 2.5 million acres of farmland, according to Marcia McNutt, director of the U.S. Geological Survey, who also addressed conference goers on Monday.

The river is ruled by decrees, rights, court decisions and laws referred to as the “Law of the River.” The keystone of these “commandments” is the 1922 Colorado River Compact, an interstate agreement for water allotments, which Salazar said was underestimated by 2 million acre feet the annual amount of water that could be extracted from the river.

“The Colorado River has been a highly litigated river over a long period of time. These compacts were put together not with the best knowledge or science. They missed the mark forecasting how much water would be available,” he said.

The river today is facing a future of a decreasing water supply due to climate change and other factors, and increasing demand for municipal, agricultural, industrial and recreational use.

In response to a question asked from the audience, Salazar said he doesn’t think the Compact will ever be opened up for negotiation: “The legacies that have been created over 89 years are so embedded in the Law of the River,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean the effort to resolve the water shortages, environmental needs, recreational opportunities, allocations to Mexico and the dry delta can’t be solved, he said.

“I’m optimistic no matter how hard these problems are, we can solve any one of these problems,” he said.

McNutt, the first female to head the U.S. Geological Survey in its 130-year history, said her mapping agency is working on mitigating the effects of dust, which decreases snowpack runoff. Eighty percent of the Colorado River’s water comes from snowpack.

“With just 5 percent less annual runoff, that’s two times Las Vegas’ annual allocation of water, 18 months of Los Angeles’ use and one-half of Mexico’s allocation,” she said.

Revising grazing policies, protecting native grasses, installing environmentally friendly fencing and digging trenches are other possibilities to help the problem, McNutt said.