(This piece originally appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of the Tutt Library Chronicle newsletter.)

As Colorado College Archivist, I am supposed to know something about the history of CC. In the past couple of years several students have asked for the details on the architects who designed Mathias Hall – architects who, according to everybody, were known for designing prison buildings. I’ve also heard from more than one student that Mathias was designed to prevent riots – that the purpose of its maze-like hallways was to stop students from gathering together in political protest.

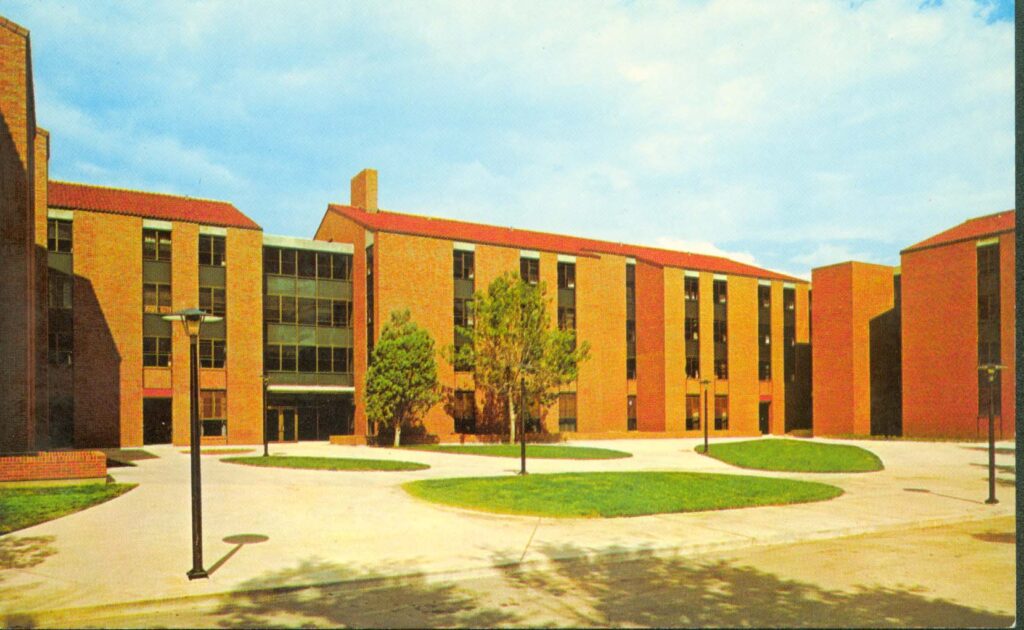

Both rumors are patently false. The Texas architecture firm which designed Mathias Hall (and Olin Hall, in 1961) – Caudill Rowlett Scott – was never responsible for any prison building. It does, however, have a historical reputation for originating design principles that led to some really ugly school structures.

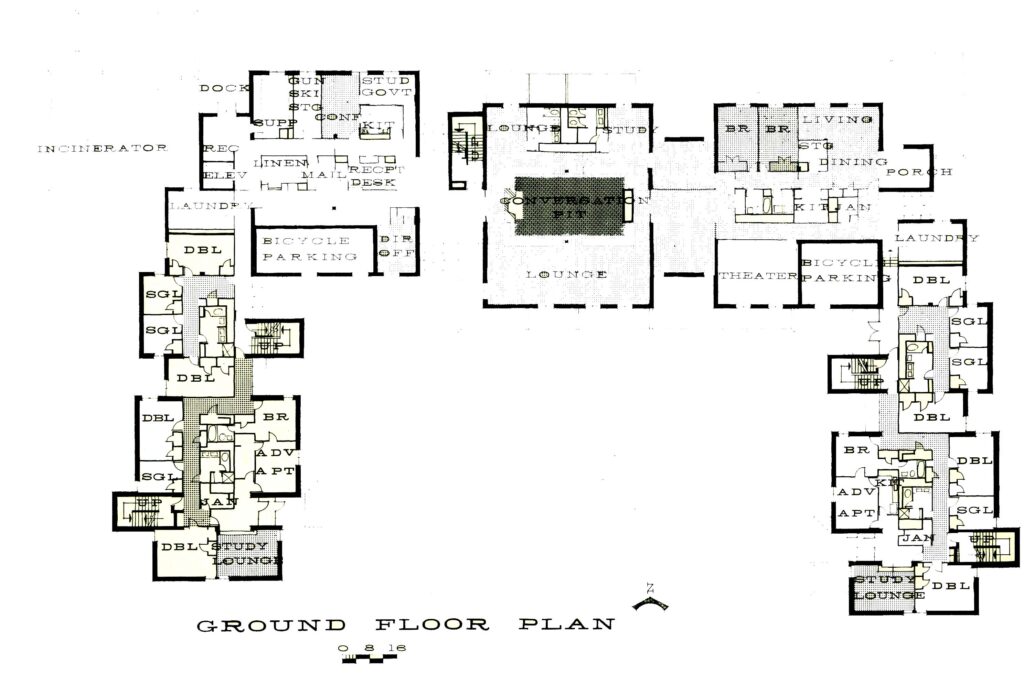

Mathias, at 123 East Uintah, was built in 1966 for a total cost of $1,700,000. It was named for Henry Edwin Mathias, a CC Geology professor and administrator. In its early years, this huge residence hall for over 300 young men was known as “Superdorm” – or, sometimes, “Superwomb,” since many of the residents had been living off campus but were required to come back to mother CC.

In 1969, by student vote, the building went co-ed – the first dorm on campus to do so. At first, the floors were sexually segregated, but by 1977 even this rule was thrown out – and in 1988, all caution was thrown to the wind – or rather, a new kind of caution came into play – and condom dispensers were installed in the hall’s bathrooms.

And now back to the building’s architects. William Wayne Caudill of CRS was a Texas architect and teacher who made educational buildings his specialty. In the 1940s he coordinated a project to optimize natural airflow and daylight in schools, and by the 1960s his firm had an international reputation for good school design. CRS branched out to hospital design, but schools remained their specialty.

An early memo from Vice President W.R. Brossman, who was in charge of the project to design the new dorm, states that the rooms should be “attractive and non-institutional.” Another report gives insight into some of the money-saving possibilities available to the architects: “The Committee is opposed to ‘gang showers’ and would like to investigate further ideas on attractive single units.” This same report also suggests “a sundeck or sunning area must be provided or else the residents will climb to the roof.”

If Brossman, or anyone on the committee, was worried about riot prevention, this was never stated in any written documentation that has survived in the Archives – and it seems unlikely that it was a major concern, since CC students were not known to riot, even in the 1960s.

In a recent article in Harvard Design Magazine (“Environmental Stoicism and Place Machismo,” Winter/Spring 2002), author and Urbanism professor Michael Benedikt credits CRS for both improving and screwing up school buildings all over the United States. According Benedikt, it was Caudill’s 1954 book Toward Better School Design that “began the school design revolution.” The book recommended natural lighting and “visual openness to the outdoors” – i.e., lots of windows. (Side note: CRS also designed CC’s Olin Hall, also known as the “Fishbowl” for its many windows.)

At the same time, however, Caudill’s core design principal were efficiency and fast construction, and over time, according to Benedikt, these principals “devolved” into those that drive the soulless school building designs – environments “barely better than a minimum security prison” – still popular today. Benedikt goes on to say that “primary and secondary education may rightly be compulsory, but this should not mean that the sites of education should be like penitentiaries.” I’m sure he would agree that college dorms have the same prerequisites.