Please note: we are updating this post as we learn more. Most recent update: March 11, 2025.

Assistant Curator Amy Brooks and Curator Jessy Randall write:

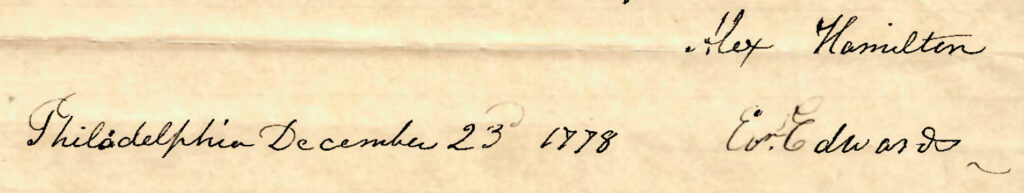

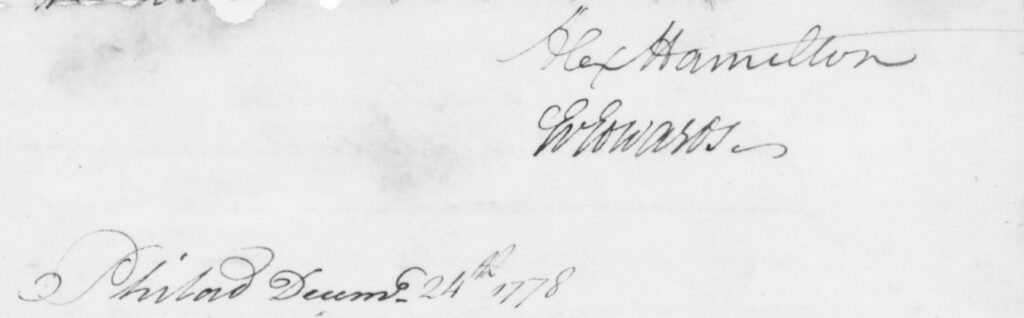

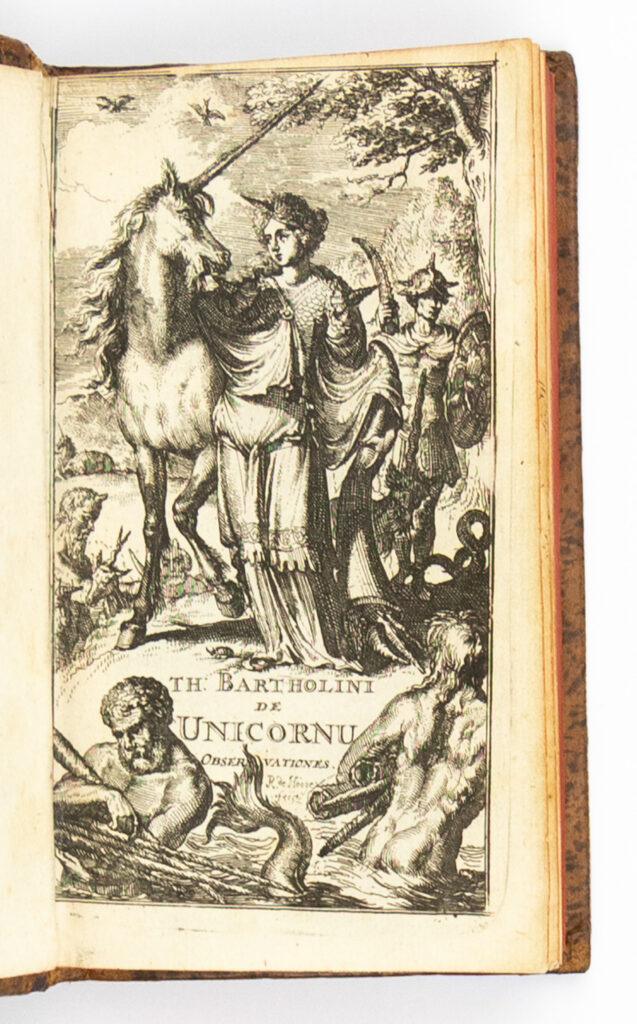

A mystery is unfolding in Special Collections. We recently discovered we have a letter, signed “Alex Hamilton,” dated December 23, 1778. Is it an original? A draft? A copy? If it’s a copy, is it contemporary with Hamilton, or later? Could it be a forgery?

Here’s the story:

On Monday, February 17, Anna Malczyk of the University of Oxford sent a research request, and we pulled out the Josiah Holmes Papers, a modest archival box of materials, gifted to Special Collections in 1963. Malczyk had discovered (through the library catalog) that the papers included two letters written by Alexander Hamilton’s close friend John Laurens. When we looked in the folder, we found the Laurens letters and — much to our surprise — an uncataloged 3-page manuscript letter signed “Alex Hamilton” and “Evan Edwards.”

Here’s a PDF of all three letters in Ms 17, Box 1, Folder 1:

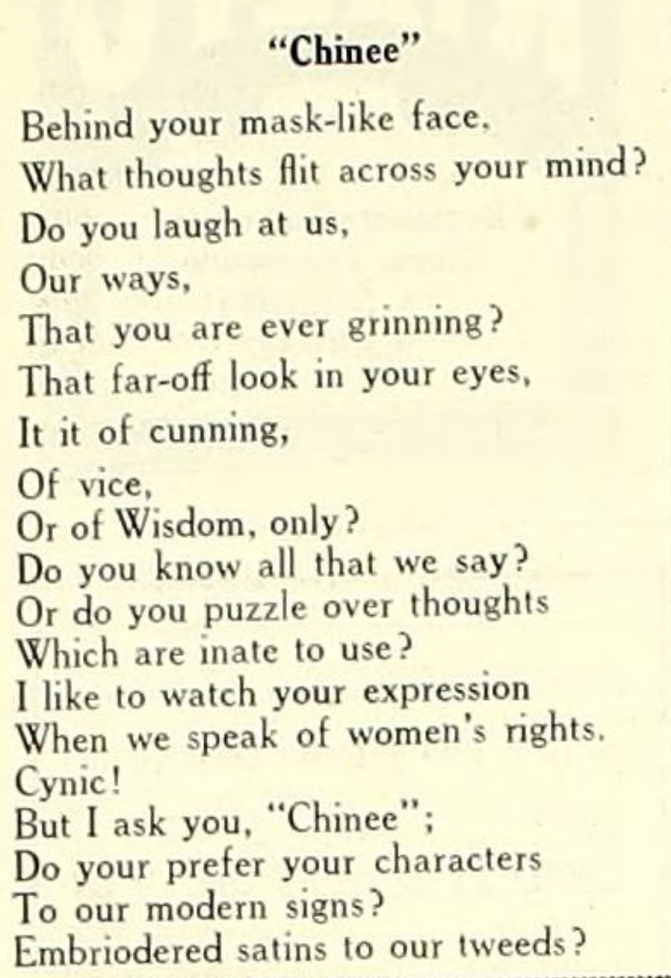

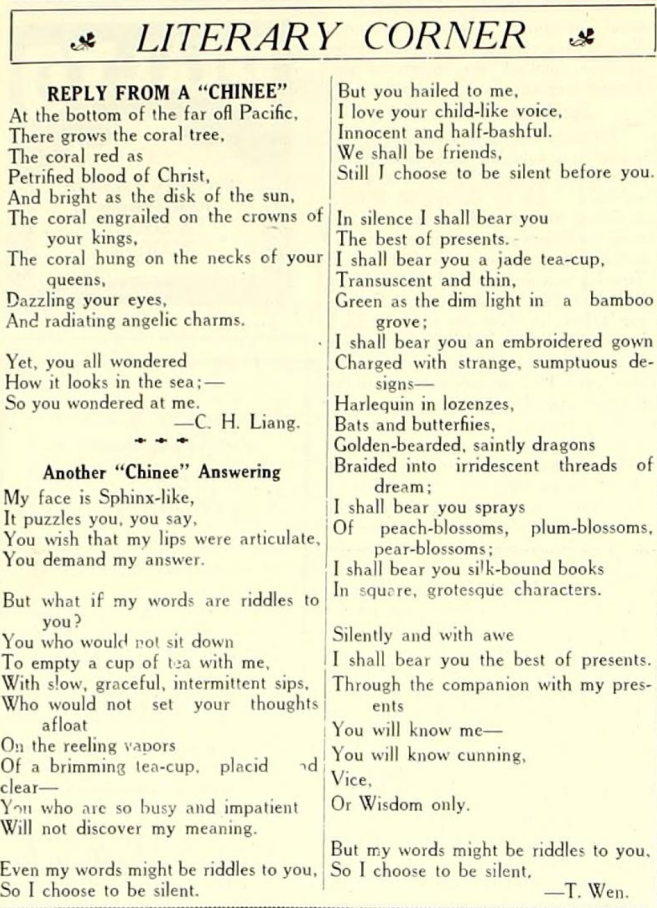

The first thing we did was read the Hamilton/Evans letter. It’s a narrative describing a duel fought on December 23, 1778, between John Laurens and Major General Charles Lee. Yes, THAT Laurens and Lee, from the musical!

The second thing we did was look up whether Alexander Hamilton ever signed himself just “Alex.” Yes, he did, and we learned that the Library of Congress (LOC) has a very similar letter to ours, dated one day later, December 24, 1778, also signed “Alex Hamilton.”

A transcription of the LOC letter is available from the National Archives. Our letter and the LOC letter have almost the same text. Both look like drafts, with cross-outs and changes. Some examples: our three-page letter has an asterisk at the bottom of page 2 after “He said every man,” leading to a note on page 3, whereas the five-page LOC letter has the note incorporated into the text on page 4; our letter has “sentiment” in one place where LOC has “opinion”; and there are several differences in abbreviations of “Colonel” and “General.”

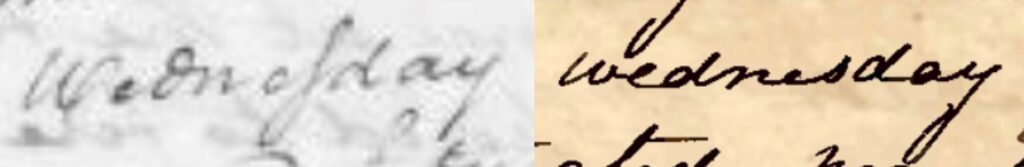

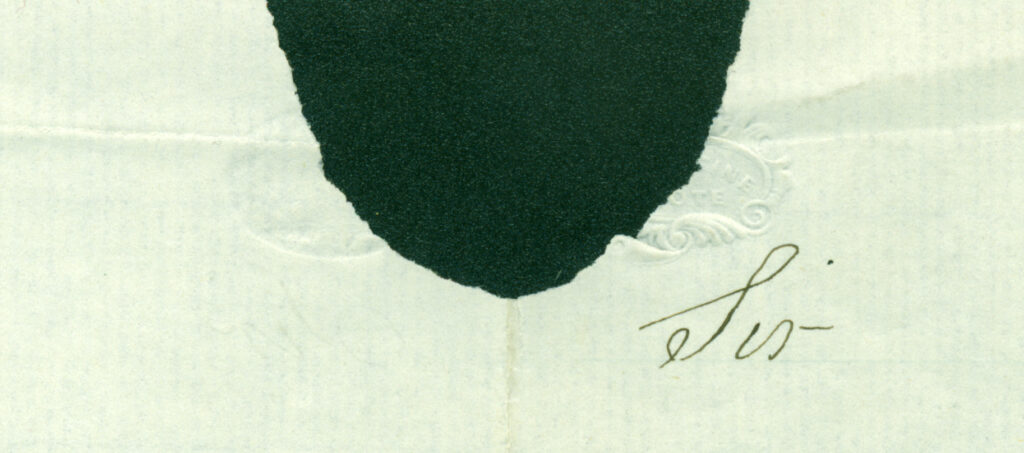

To our eyes, the handwriting of our letter and that of the LOC version seem similar, but Malczyk, who knows a lot more about it, does not believe Hamilton wrote the letter at CC. She points out Hamilton’s use of the long “s” in the word “Wednesday” in the LOC version:

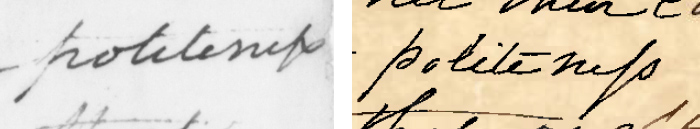

In another place, though, the word “politeness” in both the LOC and CC copies have the long “s”:

Malczyk says the letter at CC’s “handwriting style, paper and ink are not typical of the 18th century.” Papermaker Jillian Sico, however, visited Special Collections and took a close, in-person look at the paper, and believes it could be from 1780.

On the advice of CC history professor Amy Kohout, we contacted Hamilton scholar Joanne Freeman to ask for her thoughts. She responded: “Given the importance of the two seconds in a duel coming up with a mutually agreeable account of the duel after it happened, I think that your copy — dated the day of the duel — might be a first draft (with that asterisked addition) which was then put in final form in the copy at the Library of Congress. It was relatively common for the two seconds to jointly compose a final account of a duel — which was important because it would serve as the final account of ‘honor being satisfied.’ ” So we now postulate that our December 23 letter could be a first draft of the LOC’s December 24 letter, perhaps in Evans’s hand rather than Hamilton’s. (We haven’t been able to find an example of Evans’s handwriting.)

Now let’s go back to those Laurens letters, dated December 3 and 7, in which Laurens challenges Lee. Malczyk summarized the context for us:

“Major General Charles Lee was court-martialled after the battle of Monmouth in 1778 on account of his supposedly cowardly, disrespectful and insubordinate conduct [toward General George Washington]. Col Laurens was a witness against him at the trial, and when Lee subsequently continued to speak negatively of Washington, Laurens challenged him to a duel to defend Washington’s honour – quite an unusual thing to do, as generally men fought their own duels. Regardless, Laurens and Lee arranged the encounter; we see from the letters here that an original date was set, but was then postponed on account of unavoidable military business. Cols Hamilton and Edwards served respectively as their seconds, and the duel was fought on 23 December 1778. Both men fired, Laurens lightly wounded Lee, and the affair was put to an end. Typically of the time – to indemnify against future disputes – the seconds wrote an account of what happened and both signed it.”

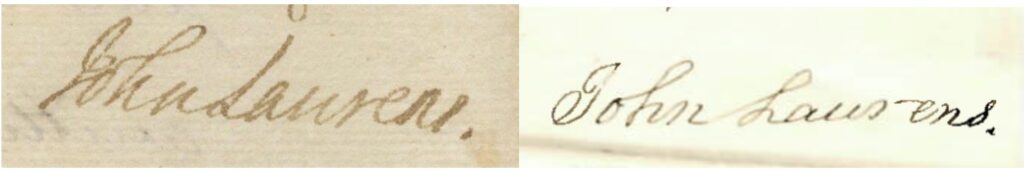

Malczyk does not believe the letter we have at CC is in Laurens’s hand. “Perhaps one needs to have been staring at his handwriting for years, but the differences jump out at me right away,” she says.

(To add to the uncertainty, it’s widely known that Laurens sometimes wrote with his left hand and sometimes with his right. See this tumblr for examples. But neither the left nor right handwriting matches what we have.)

Malczyk points out, too, that letters written a few days apart would not both be on a single sheet of paper. When we asked if they could be drafts, she said this would be unlikely, as people don’t usually sign their drafts — and that in general, Laurens wasn’t known for making or keeping drafts. Papermaker Jillian Sico took a close-up look at this letter, too, and recognized the paper as bleached, a 19th century process. So this letter is likely a copy made decades after the original. There’s a partly-missing blind stamp at the top of the Laurens letter that looks like this when we unfold the sheet:

We think it says “ine” at the top right and “ote” at the bottom right. Likely an ownership stamp, but whose? Tantalizingly, it is only partly removed, not completely — why?

All that said, Malczyk thinks “the content itself, the ‘voice’ of the letters, and the structure certainly do fit Laurens, so my suspicion is that somebody made this copy directly from the original, preserving the content and layout. This is especially important as I’m not sure the location of the original is known, or if it even exists anymore – so this remains a valuable historical record.” Indeed, as far as we can tell, the original Laurens letter is nowhere to be found, so our copy may be the only one extant. Until recently, Dianne Durante’s incredibly thorough blog post on the Lee-Laurens duel stated “John Laurens issued a challenge to Lee (we don’t have it).” Her post now additionally directs readers to the post you are reading right now.

Multiple print sources quote Laurens’s challenge to Lee. The earliest we’ve found is Memoirs of the Life of the Late Charles Lee, Esq. Second in Command in the Service of the United States of America During the Revolution, published 1792. In it, Lee quotes, or paraphrases, the letter he received from Laurens (Lee uses quotation marks but has changed the point of view to third person): “…that in contempt of decency and truth, he [Lee] had publicly abused General Washington, in the grossest terms … the relation in which he [Laurens] stood to him [Washington], forbade him to pass such conduct unnoticed; he therefore demanded the satisfaction he was entitled to, and desired, that as soon as General Lee should think himself at liberty, he would appoint time and place, and name his weapons” (p. 47). Versions of this phrasing appear in multiple print sources for two centuries, either without citation or citing previous print sources. The only citation we have found to an actual autograph letter is in Gregory D. Massey’s John Laurens and the American Revolution, published in 2000. Massey cites … wait for it … the copy here at Colorado College. (See chapter 6, note 59, page 264.)

We have lingering questions. How did the Hamilton/Evans and Laurens letters end up with the Holmes family in the first place? Was the family connected to these Revolutionary War personages? We’ve looked at biographies of Hamilton, Evans, Laurens, Lee, and Washington, and cannot find a Holmes connection. And yet as far as we can tell, the Holmes family weren’t autograph collectors – all other materials in the collection are related to the family, including an 1832 letter from John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) to Josiah Holmes (1790-1860). So, if any of the letters are forgeries, deliberately intended to trick a buyer, who benefitted?

Whatever they are, the letters are a fine recounting of a dramatic (and thankfully non-lethal) duel. Maybe a historian and/or Hamilton super-fan will shed additional light on our mystery in the future.

.jpg?mode=max&w=1)