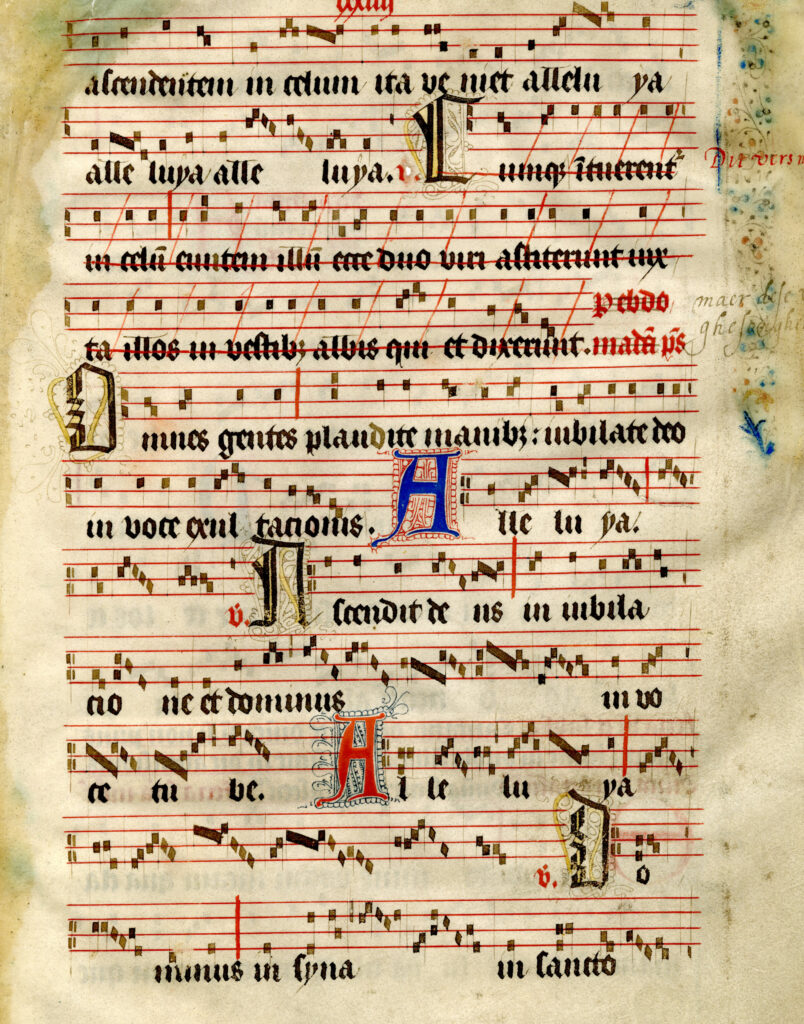

Students in “The History and Future of the Book” half block class January 2026 worked together to write, illustrate, design, set type, print, and bind 24 numbered copies of Sheep Are Rectangular, a bestiary of imaginary book-related creatures.

Steve Lawson (Access Service Librarian and co-instructor), Jillian Sico (Printer of the Press), and I (Curator of Special Collections and co-instructor) are CRAZY PROUD of this.

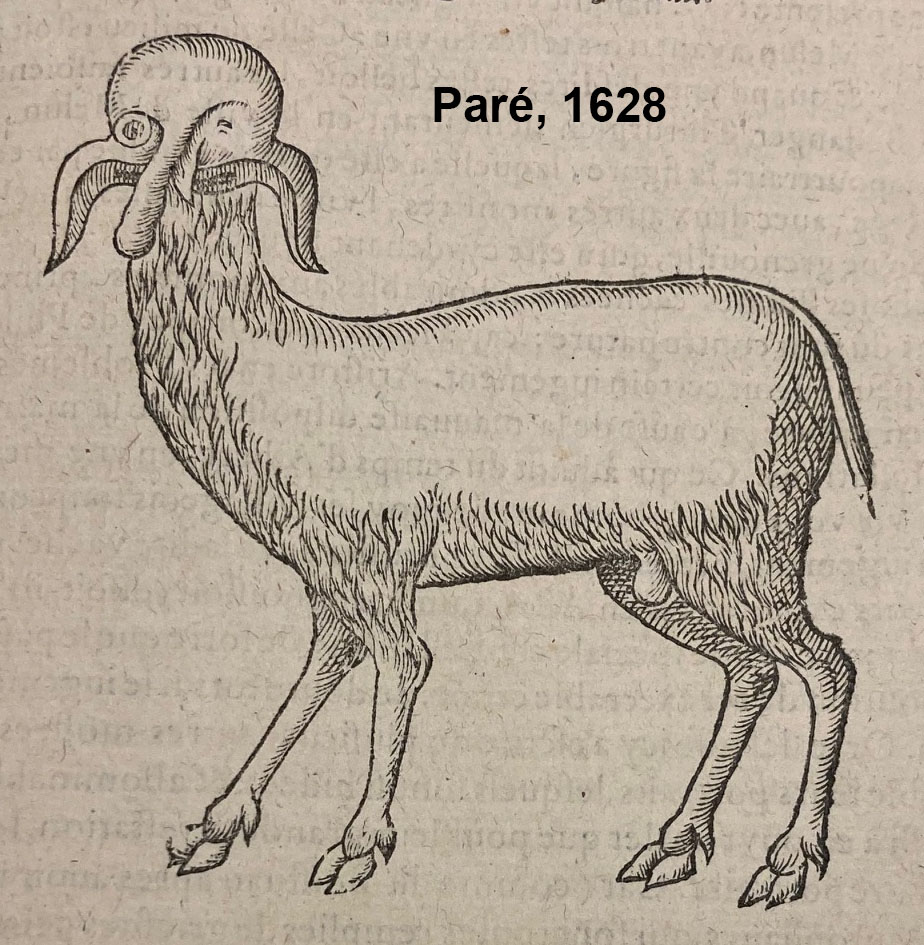

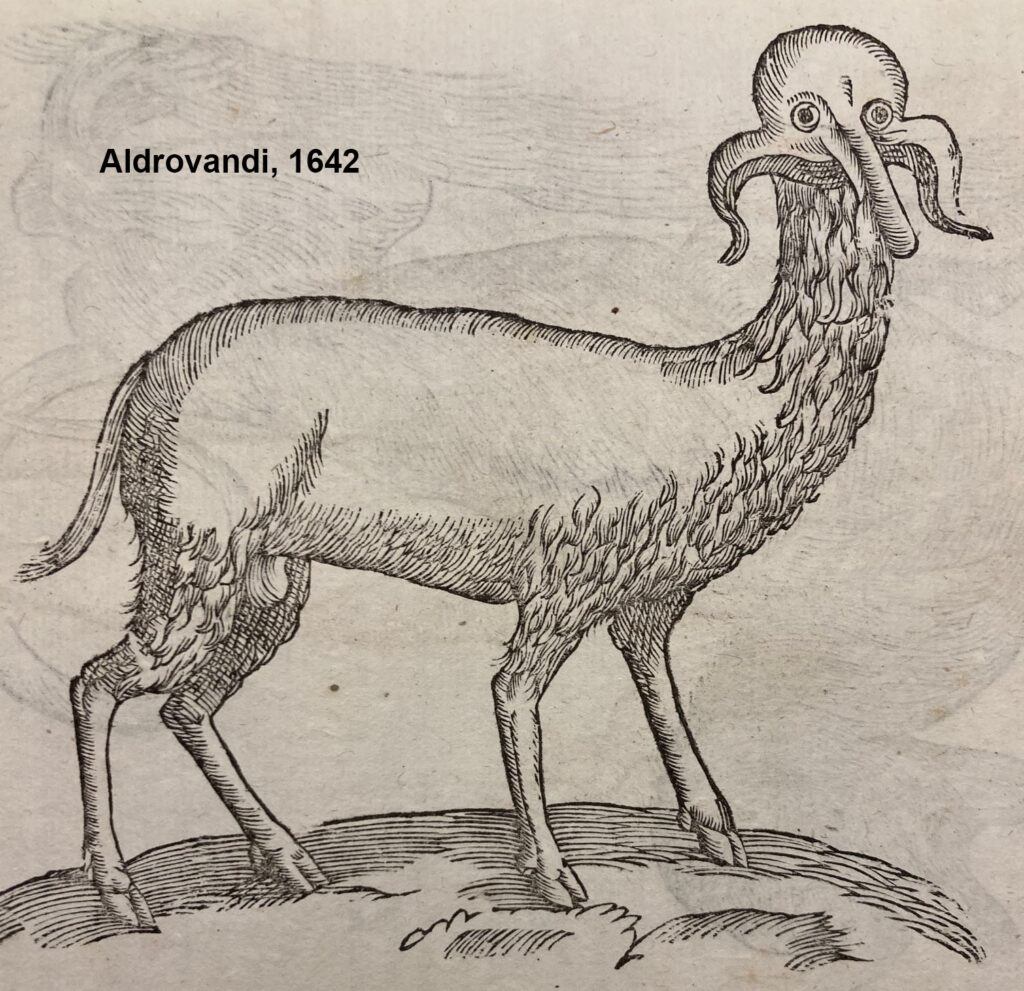

The title of the book comes from something Carol Neel, CC history professor, says to her medieval history students: that books are rectangular because sheep are rectangular. Although this may not seem to make sense at first, what she means is that a sheepskin, when removed from the sheep and trimmed for use as parchment, is rectangular. The efficient use of as much sheepskin as possible means that books, too, are rectangular.

The creatures are: incunababie, boustrophedon, dog ear, bookwyrm, common pica, illuminated lightning bug, and title tots.

Students in the half block: Paikea Kelley, Hope Lowden, Senaida Vigil, Kian Stone, Ethan Kirschner, Anna Crossley, Perry Davis.