We have dozens of 19th and 20th century dance cards in the Colorado College archives. (The examples above, both from 1912, belonged to CC alumnae Dorliska Crandall and Katherine Constant.) Students find the cards intriguing, and ask lots of questions about them: how did this dance card thing work, exactly? Did you fill out your dance card in advance of the dance, or at the dance, or afterward as a souvenir? Almost all our dance cards are from women’s scrapbooks. How did men keep track of their dance partners? Did they just keep the list in their heads?

V. Persis Dewey’s 1918 pamphlet “Tips to Dancers: Good Manners for Ballroom and Dance Hall” holds the answers. Dewey tells us, in no uncertain terms, the proper use of dance cards:

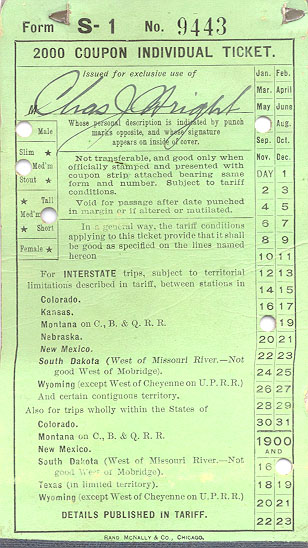

The programs are distributed at the door, in the cloak room, or during a grand march. It is the duty of the man to make out the programs for the lady whom he has escorted to the dance and for himself. It is best to make out the programs all at once and as early in the evening as possible.

In filling out a program, the man should write his name on the first line of his lady’s program, and her name on his. To indicate their dances, a double cross xx should be used.

At a program dance where the men and women come separately, each one keeps his or her own program. When the man invites a lady to dance he writes his name on her program after the number they decide to dance together.

These conventions, breakable as they must have been, suggest that our dearth of men’s dance cards comes less from men not using them and more from men not saving them in scrapbooks. And indeed, with a bit of sleuthing, I did find several dance cards belonging to Eugene Gordon Minter, CC class of 1930. Some of these cards have erasures and corrections, suggesting that Minter’s original dancing plans might not always have come to fruition.

Both women’s and men’s dance cards include both women’s and men’s names. Mr. Dewey does not speak of same-sex partners in his pamphlet on dance etiquette, but it seems that same-sex partners were a normal and natural part of formal dances in the dance card era.

I think I would have really dug this whole dance card thing in high school and college, but maybe not so much in middle school, when it seems likely my dance card would have been filled with names like “I.P. Freely,” “Seymour Butts,” and “Mr. Bates.”

Sources: Dorliska Crandall scrapbook, CC Archives box 947; Katherine Constant collection, box 545; Eugene Gordon Minter scrapbook, box 923.