In the 1980s, Stephen Blumberg stole thousands of books and manuscripts from American libraries, amassing a collection worth millions of dollars. (For the full story, see his Wikipedia entry or the “Bibliokleptomania” chapter of Nicholas Basbanes’s A Gentle Madness.)

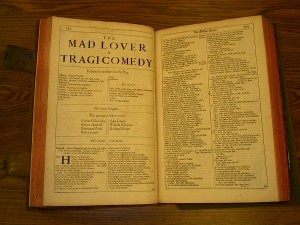

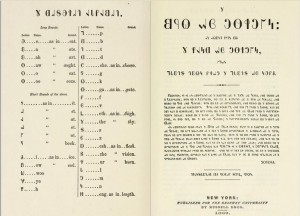

Colorado College was one of the many stops on Blumberg’s cross-country book-stealing tour. He stole at least two books from us. One of these was no big deal, a 1930s pamphlet on Bent’s Fort, easily replaceable. The other, however, was quite rare: Henry Villard’s The Past and Present of the Pikes Peak Gold Region, published in 1860. Currently, it’s held in only a handful of U.S. libraries and isn’t available from any dealer. The FBI valued the CC copy, in its crummy modern binding, at $10,000.

Colorado College was one of the many stops on Blumberg’s cross-country book-stealing tour. He stole at least two books from us. One of these was no big deal, a 1930s pamphlet on Bent’s Fort, easily replaceable. The other, however, was quite rare: Henry Villard’s The Past and Present of the Pikes Peak Gold Region, published in 1860. Currently, it’s held in only a handful of U.S. libraries and isn’t available from any dealer. The FBI valued the CC copy, in its crummy modern binding, at $10,000.

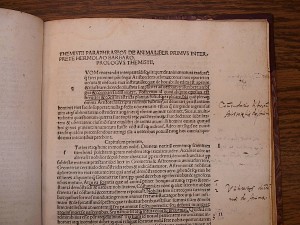

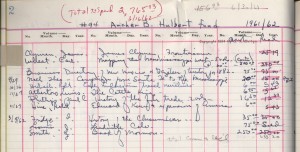

Blumberg may have stolen as many as a dozen books from our library, but only these two were recovered. Library staff worked with the FBI to get the books back. It was particularly complicated because Blumberg not only removed or covered over library ownership marks from books, he also added false library marks. So, for example, a book stolen from Harvard might get a University of Michigan bookplate slapped onto it, and then a “withdrawn” stamp on top of that.

As was his wont, Blumberg used his own saliva to remove the CC bookplate from our copy of this book. (He frequently chose to lick bookplates off, whether he was in library reading rooms or at home.) Nevertheless, the FBI tracked the book down, and it was returned to CC after Blumberg’s 1991 trial. He spent almost five years in jail. Since 1996, he has been convicted twice more for similar thefts.

As was his wont, Blumberg used his own saliva to remove the CC bookplate from our copy of this book. (He frequently chose to lick bookplates off, whether he was in library reading rooms or at home.) Nevertheless, the FBI tracked the book down, and it was returned to CC after Blumberg’s 1991 trial. He spent almost five years in jail. Since 1996, he has been convicted twice more for similar thefts.

Because researchers often want to see the book that Blumberg stole, but can’t always remember the name of it, we now state in our catalog record that our copy of the Villard book was “temporarily part of the Blumberg Collection.” It’s a good book to bring out with classes when we want to talk about the ethics of book collecting, and always sparks an interesting discussion.